The Early Years and the Birth of Photography - The 19th Century

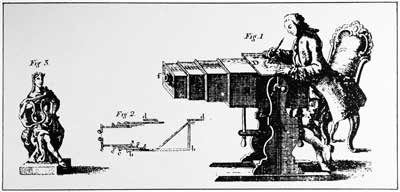

Camera Obscura

Which came first, the camera or the photograph? Well, that is easy; the camera preceded the photograph by hundreds of years. The camera obscura is a box or maybe a room, with a pinhole, or later a lens, that was used to project an image on the opposite wall or simply on a piece of paper. It was often used as an aid in making sketches.

It is believed that the Chinese made the first ones and then later used by the Arabs in the tenth century, but it was Leonardo da Vinci that first described the camera obscura in detail in the fifteenth century. The inventors of photography use the camera obscura as the basic tool in trying to fix the image on a permanent material.

Louis Daguerre

The credit for producing the first image using light goes to the Frenchman Joseph Nicephore Niepce. He was able to make an image using bitumen of Judea dissolved in a solvent. After being exposed to light, the material was washed with oil of lavender to leave an image where the light had hit. The exposure time was around eight hours and the image then faded rather quickly.

Niepce was introduced to Louis Jacques Mande Daguerre in 1826 by a Paris optician named Chevalier. They formed a partnership but Niepce died in 1833. On January 7, 1839, the Daguerreotype process was introduced to the public for the first time. Daguerre used a copper plate coated with silver. The copper plate had to be polished, iodized, exposed to light in a camera, and then developed in a light tight room, called a darkroom. This was the basic principle of photography for years to come.

Daguerre was able to strike an interesting deal with the French government which gave him a guaranteed pension for life in exchange for giving the patents to the world. Before long there were Daguerreotype studios in every major city in the world and for the first time, just about anybody could walk in and have a portrait made.

William Henry Fox Talbot

William Henry Fox Talbot was an Englishman who lived from 1800 until 1877. He was a scientist, mathematician, botanist, Orientalist, etymologist, and a Member of Parliament. One day in 1833, while on vacation at Lake Como in Italy, he became frustrated with his efforts at sketching a scene. He began to imagine what it would be like if the images could be permanently fixed to paper without the need of pin and ink.

When he returned home to England and Lacock Abbey, he began experimenting with different light sensitive chemicals and within a few years had made several images that could correctly be called the first photographs. It wasn’t until after Louis Daguerre had made a public demonstration of his Daguerreotypes in France in January of 1839 that Talbot announced his photographs.

Unlike Daguerre’s photos which were unique and could not be easily copied, Talbot used a negative/positive process that allowed for multiple originals to be made at a time. Eventually Talbot’s Calotypes became the standard method of making photographs for at least the next one hundred years.

Glass plates

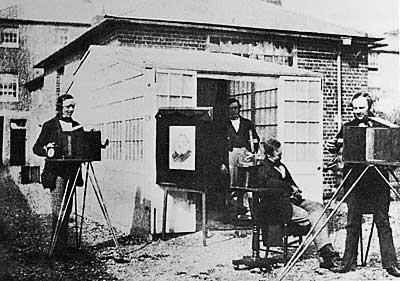

Eventually Daguerreotypes became obsolete when newer processes became available. Specifically a system using coated glass plates which could then be printed onto paper became more practical and of higher quality.

The photographer had to coat the glass with a light sensitive emulsion, expose the plates in a camera, and process the plates, all before the emulsion dried. This was known as the wet-plate system. The system worked well in the controlled environment of a studio and darkroom, but became a real challenge for outdoor or location work. Photographers who travelled the western United States documenting the environment and natural resources during the wet-plate era had to be tough and resourceful.

The wet plate era began around 1855 and had pretty much passed to history by 1900.

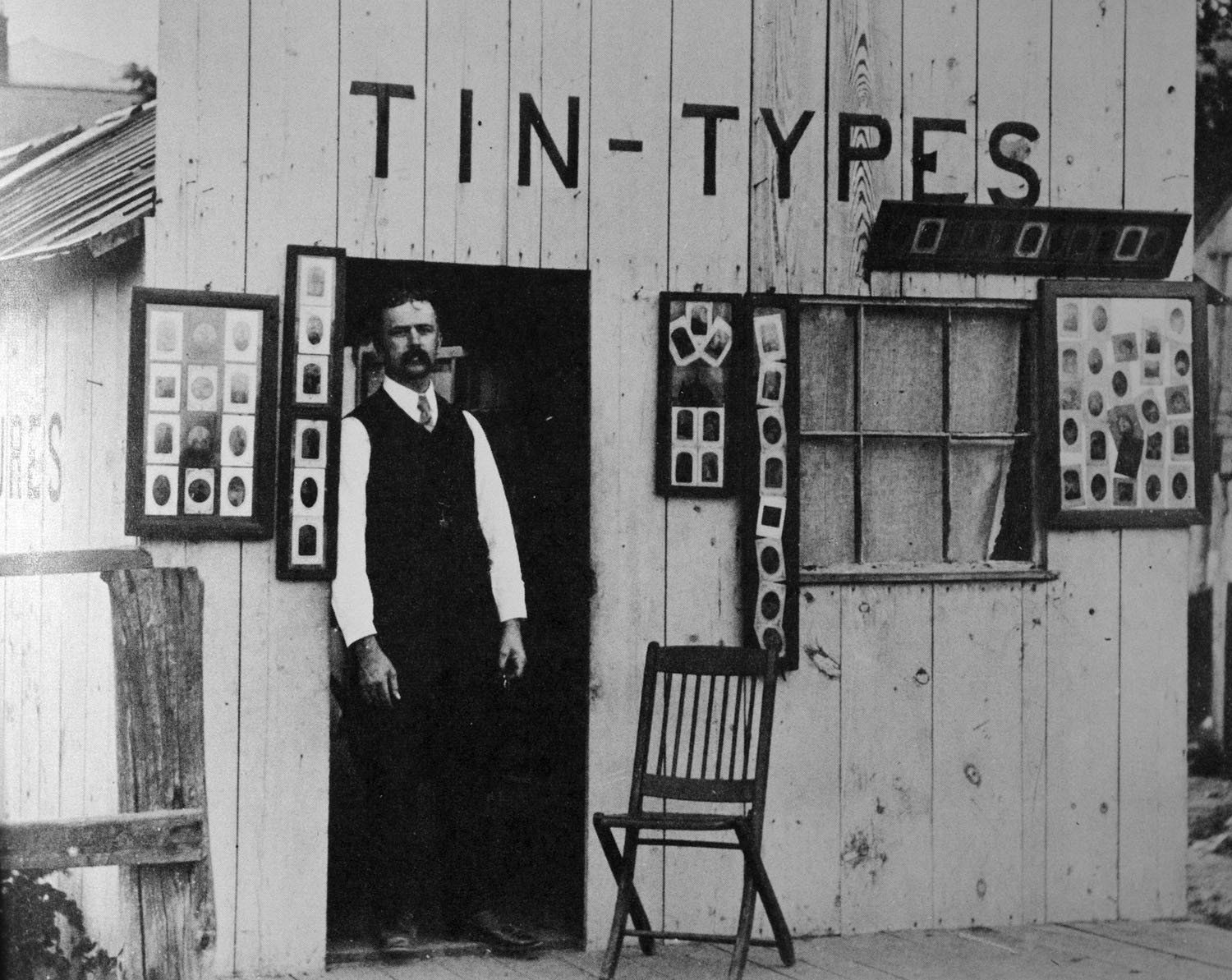

Tintypes

Ferrographs or ferrotypes are more commonly known as tintypes. Tintypes were developed in the 1850’s as a cheaper alternative to the Daguerreotypes and the similar Ambrotypes. Daguerreotypes were printed on copper with silver plating. Ambrotypes were glass mounted over black paper or cloth. Tintypes were printed directly onto the metal backing. The main advantages of the tintypes were that they were cheap and tough. They could be mailed or carried in a pocket and they have proven to be quite durable with many tintypes still around in good condition.

They were not actually tin but steel that had been blackened. The image was actually the emulsion which was slightly lighter color than the black background. We are used to seeing a black, gray, or colored image on white paper, so tintypes always look very dark.

Each image is unique in that there is no negative. Since they were on metal, there was no paper to dry which made developing a simple and quick process, sort of the 19th century version of a Polaroid instant print.

Tintypes were generally delivered in a paper window envelope that served as a frame or mat. There are many tintypes still around, but the paper mat is generally missing due to age. The era of the tintypes was from around 1855 until the end of the 19th century, though it is possible that some were still being made as late as the 1920’s, especially in third world countries. If you have tintypes, they can generally safely be dated somewhere around 1865-1880.

Pioneer Photographers

Photography during the wet plate era was not for the weak, especially once the photographer was outside the friendly confines of the studio and a permanent darkroom. The glass plates had to be carried to the location, usually in a wagon or on a pack mule. A light proof tent had to be set up where the plates could be coated with the light sensitive emulsion. The image had to be exposed in the camera and then developed before the emulsion dried. In warm weather this could be a matter of minutes.

Even under these circumstances, a number of great photographs were made. Many of the early images we associate with the American west were made this way. Some famous American photographers are associated with places and events.

Matthew Brady was a portrait photographer in New York City. He opened his New York studio in 1844 and a few years later added one in Washington DC. He photographed many politicians and public figures including Abraham Lincoln who he photographed many times. The image of Lincoln on the US one cent coin was taken from a photo by Matthew Brady.

When the US Civil War broke out in 1861, he assembled crews of photographers with portable darkrooms on horse-drawn wagons to document the war. He was under the impression that there would be a big demand for the photos when the war was over. It turned out that after the war, Americans had no interest in seeing photographs of it. He was unable to sell the photos and eventually went bankrupt because of the money he had spent hiring crews and buying equipment. He donated the glass negatives to the Library of Congress and they are now considered a national treasure.

Another pioneer photographer was William Henry Jackson. After his stint in the military during the Civil War, along with his brother, he opened a photography business in Omaha, Nebraska. One of their clients was the Union Pacific Railroad. He documented the building of the railroad west and the sights along the way. His photographs were used on travel posters to sell train tickets. It was Jackson’s 11x14 wet plate photographs that motivated Congress to designate Yellowstone the nation’s first National Park.

He had a long and distinguished career as a photographer, painter, and publisher. The SS William H Jackson was named after him as is Mount Jackson in Yellowstone. He died at age 99 in 1942. He is buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

Dry Plates

Many attempts were made as early as 1855 to either keep the emulsion wet longer or allow the plates to be used after they dried. The first successful dry plates were introduced in 1873 in England and by 1878, several manufactures were producing factory coated glass plates that could be stored, exposed, and processed at a later date without the need for an onsite darkroom.

The next step in the evolution was coating the emulsion on a flexible material. The challenge was finding a transparent material that would support the photographic emulsion. In the early 1880’s an American named George Eastman introduced a flexible paper that could be made transparent by waxing or oiling after being processed. At first it was available only in cut sheets, but in 1885 W.H. Walker designed a roll-holder that allowed a roll of film to be used with a plate camera. The first rolls of film were sufficient for 24 exposures. This was much lighter, more compact, and not as breakable as 24 similar sized pieces of glass.